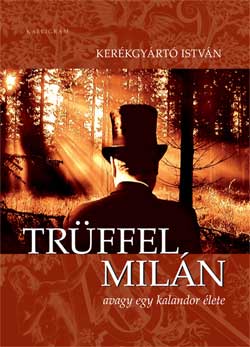

Trüffel Milán

A regényről megjelent kritikák

Hungarian Literature Online - 03. 02. 2011.

Hungarian Literature Online - 03. 02. 2011.

http://www.hlo.hu/news/the_sadness_of_a_con_man

The sadness of a con man

István Kerékgyártó: Milán Trüffel, or the Life of an Adventurer

Our nostalgic feeling for the piping days of peace is so insistent that it will soon cease to have anything to do with the real story of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. This nostalgia is the topic and the tone of István Kerékgyártó's novel, Milán Trüffel, or the Life of an Adventurer.

"He looked as if he had come from the world before the war", someone says about Milán Trüffel in a police statement. Born in 1876, Trüffel's adventurous life ended before World War I. The novel begins in the year 1933, when Trüffel comes back to Budapest. While he watches the demolition of the Tabán district of his childhood (a Bohemian district destroyed in order to facilitate urban planning), he reminisces about his life. In the meantime, the police is after him. We learn all this from police documents like the one quoted above.

The period from the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 to the outbreak of World War I was that of economic development, relative prosperity and lack of war, yet there are other reasons why the writer and the reader today feel a certain phantom pain when thinking about those times. István Kerékgyártó's novel gives voice to everything that we love about that era. Milán Trüffel, who trains himself to become a "professional hedonist" is a specialist of the joys of life: he dresses with elegance, eats like a gourmet and makes love with the refinement of a connoisseur (and sometimes mixes these two latter activities masterfully). The novel, constructed as a chain of episodes, is leisurely like the 19th century itself: although there is no lack of adventures on the pages of Milán Trüffel, there is always time for the lengthy tasting of wine, for a detailed and appetizing fish soup recipe and the description of the latest fashion, and of course, of love practices. How could there not be: the reason for Trüffel's roguery is precisely to be able to live a life of enjoyment, not that being a con man is not a peculiar enjoyment in itself. Although the novel bears the characteristics of a picaresque novel, the episodes are not interchangeable, and this is not only because of the fact that the stakes tend to rise in each subsequent chapter. While our hero (and it is rare that the word 'hero' should be so adequate for the protagonist of a contemporary novel), after a childhood in the Tabán district of Buda, travels around the Monarchy, as well as Italy, France, North and South America and Africa, turns up in musty jails and fancy villas, plays the count, the chancellor or the wandering actor, the novel also puts on the disguise of a novel of education.

While we learn a lot about the rich life of the Monarchy through the story - what's more, the confession - of a con man, the novel intimates that cheating in style is also the trade mark of the era. The pre-war world was particularly well-suited for cheating; the happy days of peace are gradually exposed as a world of make-believe. Trüffel's main instrument is pretence: his clothes, his manners, his elegantly applied skills enable him to pocket huge sums. Yet Trüffel's success as a con man is enabled by the corruption of the world around him: often the only reason why he is not exposed is that the sum he steals had been intended for bribery. Trüffel appears in his own narrative as a Robin Hood who does not rob the rich to give money to the poor, but only to one poor man, the ex-pauper: himself. The con man who builds up his career in an intellectual way is a real self-made man, a born capitalist, and although he exploits his age, the age determines him in its turn. To that extent, the novel of education is a disguise: while his life is a perpetual show, the permanence of his personality rests with his "professional hedonism".

A con man who has style can only be successful in an era which has style, and the defining stage sets of the period suggest as much. The circus, the orpheum, the wandering troupe, as well as politics and even journalism appear to be arts of make-believe.

Besides the adventures, the tension in the novel arises from the hero's inner conflict that although he is a master of the art of make-believe, his success depends on keeping his secrets. The sadness of the con man also derives from this: we can never guess the real tricks, and if we do guess them, we start to suspect that perhaps the narrative itself is the trick. This is what gives weight, if not dramatic force, to this cheerful story which darkens only towards the beginning of World War I: while reading this memoir we may feel that we are committing an indiscretion that the author himself all but desires. As if Trüffel was aching to be caught.

In an endless mirror game of nostalgias, with a thoroughness worthy of a lexicon and with daring imagination, Kerékgyártó's novel erects a monument to a world that has perhaps never existed. And it is just as much in vain to ask whether this age had ever existed as such or whether it is only us who want to remember it as such as to ask whether we can believe what a con man says.

szerző: Turi Tímea

István Kerékgyártó: Trüffel Milán, avagy Egy kalandor élete

Pozsony: Kalligram, 2010

[ « Vissza ]